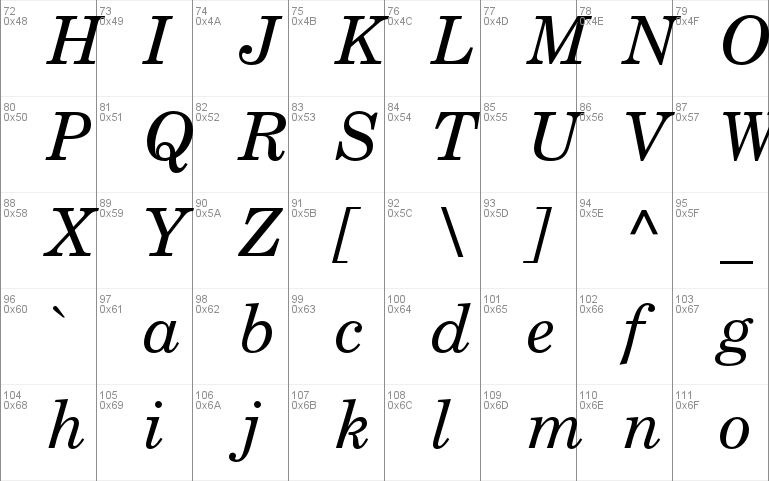

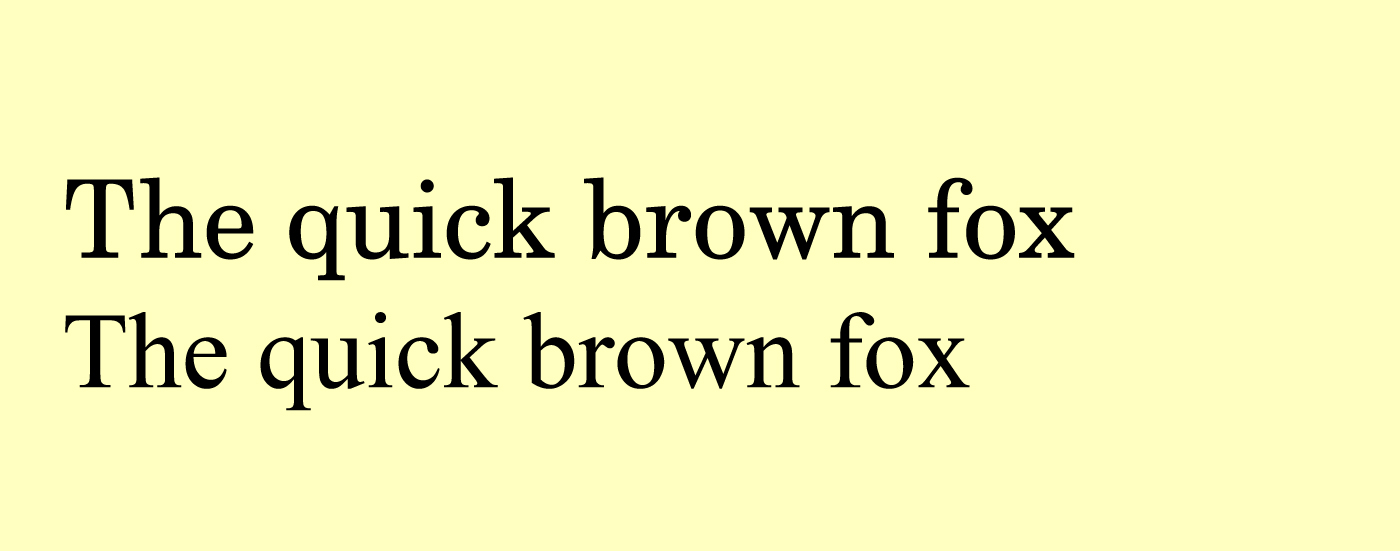

You can improve your chances by making your briefs typographically superior. Reading that much is a chore remembering it is even harder. The briefs, opinions of the district courts, essential parts of the appendices, and other required reading add up to about 1,000 pages per argument session. The 7th Circuit has offered this explanation for its choice: Courts of Appeals for the 5th, 7th, and Federal Circuits have long used and endorsed Century-family fonts. Likewise, Rule 33(1)(B) of the Supreme Court’s Rules states that the text of all major documents, including briefs, “shall be typeset in a Century family ( e.g., Century Expanded, New Century Schoolbook, or Century Schoolbook) 12-point type.” Supreme Court publishes its opinions in Century Schoolbook. While you may not immediately recognize the name Century Schoolbook, you’ve been reading legal opinions in this font since your first year of law school. Times New Roman and Courier, by contrast, made the “C list” of “questionable” fonts for lawyers. The book “Typography for Lawyers,” for example, ranks Century Schoolbook on a short “A list” of fonts. The font you’re currently enjoying is Lato.)Īmong its attractive features, Century Schoolbook is “highly readable, yet commands an air of authority with letters that take up more space than Times New Roman.” It has even been called the “crème-de-la-crème of legal fonts.” (Editor’s note: Unfortunately, we have no Century family fonts installed on this WordPress theme. For their legal writing needs, lawyers can do much better.įonts in the Century Family = Better Readability and Retentionįor good reason, fonts within the Century family have emerged as the favorite of many legal writers. Ultimately, though, neither Times New Roman nor Courier was designed for legal writing. This is, in part, because “hen every character is the same width, the eye loses valuable clues that help it distinguish one letter from another.” It is also more difficult to read than newer, better-designed fonts. Like all non-proportional fonts, Courier is not an efficient use of each page because it takes up more space than necessary. Recently, governments and private companies have started to reject Courier as an old, outdated, and “clunky” font. From there, like Times New Roman, it gained popularity because of its ubiquity, not its attributes. Eventually, it became the basic font for computer processing. Perhaps it was because writers found it familiar. Even after typewriters began to die out in the 1980s and 1990s, however, Courier stuck around. In the 1950s, this function may have seemed modern and streamlined. With Courier font, the letters are all the same size-in typography terms, “non-proportional.” With an “i” taking up the same space as a “w,” for example, it allowed a typewriter to use a white-out key that was the same size for every letter. Instead, its purpose was to make it easier to edit documents typed on typewriters. Ĭourier’s original purpose had even less to do with reading retention than Times New Roman. Courier was developed by IBM in the 1950s, but it became the standard typewriter font in the 1960s. This is Courier New, another font that many North Carolina lawyers use. As one commentator has remarked, Times New Roman is “the font of least resistance.” It “is not a font choice so much as the absence of a font choice.” It is the beige of fonts. Today, for whatever reason, Times New Roman has become the standard, including for North Carolina lawyers. The emphasis was on speed, not retention. It was not, however, designed for intensive reading-for example, reviewing lengthy briefs. Another benefit of this closely spaced font was that it left ample space for advertisements. The letters in Times New Roman are narrow, closely spaced, and designed to force readers’ eyes across the page as quickly as possible. It was designed for a specific purpose: to allow speed-skimming the newspaper’s articles. Times New Roman was developed in the 1920s by a British newspaper, The Times of London. This is Times New Roman, the font that most North Carolina lawyers use for their legal writing. The second part briefly describes how fonts within the Century family increase readability and retention-features that can give lawyers a competitive edge. The first part discusses the current font norms for North Carolina lawyers, and why the fonts favored by those norms are not optimal for legal writing. We know what you’re thinking: Why should I care about fonts? The authors of this article-an appellate judge and a few litigators-would like to answer this question in two parts.

By Judge Richard Dietz, Drew Erteschik, Clark Tew, J.M.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)